This website is about stepped wedge trials, but to understand these you need to understand the randomised controlled trial. Randomised controlled trials have had a huge impact in helping to shape the delivery of health services since their introduction in 1948. So what are they, and what makes them so important?

Clinical trials

First, what does the word “trial” mean in health research? The World Health Organisation provides a helpful definition: “clinical trials are a type of research that studies new tests and treatments and evaluates their effects on human health outcomes”. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors go further: a clinical trial is “any research study that prospectively assigns human participants or groups of humans to one or more health-related interventions to evaluate the effects on health outcomes”.

These definitions are deliberately broad. In particular, while you might associate clinical trials with pharmaceutical research, the “treatments” or “interventions” in the definitions above can be just about anything that could plausibly influence your health: besides a drug treatment this could be an educational package, an activity such as gardening or playing football, a change to the way your General Practice computer system works, or any of a million other ways to intervene to improve health outcomes or the delivery of health services.

Randomised and controlled

What about the “randomised” and “controlled” bits of a randomised controlled trial? For many researchers these are central to what a “trial” really is. “Controlled” means having a comparison by which to judge how well a new, proposed intervention works. The “control” might be the current standard of care for the people whose outcomes you are studying. (In a drug trial the control is often a placebo pill, designed to look and taste identical to the pill containing the active drug.) Some people in the trial are given the new intervention, and some are given the control.

If the choice of giving a trial participant the intervention or the control is made randomly, then the trial is described as “randomised”. This simple idea turns out to be incredibly powerful. The first time randomisation was used in a trial – a study of streptomycin as a treatment for tuberculosis, funded by the UK Medical Research Council and published in 1948 – is celebrated as the beginning of a revolution.

The benefits of randomising

Randomisation achieves something very special: it means that every participant in the trial has the same chance as any other of receiving the intervention, and the same chance as any other of receiving the control. This means that, apart from the intervention itself, there are no systematic differences between people in these two groups (there are random differences, but we can handle those with a statistical analysis of the results: statistics is the science of handling random variation).

Imagine doing a trial where all the participants you recruit in the morning are given the intervention, and all the participants you recruit in the afternoon are given the control. These groups of people might be fundamentally different in any number of ways, so it would be a mistake to conclude that differences in their health outcomes were entirely due to the intervention. But by randomising we avoid this problem.

Concealing allocations

Now, one way in which the two trial groups could still end up differing systematically would be if the researchers who recruited new participants knew which group the next recruit would be allocated to. This knowledge could consciously or unconsciously bias the researchers in deciding whether to even approach a particular individual to take part. But if the allocation is determined randomly then there is no way for researchers to work out what the next allocation will be (unless they have seen a pre-prepared schedule of the allocations). This is known as “allocation concealment”, and is another key benefit of randomisation.

Imagine doing a trial where new participants are recruited in a constant stream, and allocations simply alternate between the control and the intervention. It may be less obvious here than in the morning/afternoon example that there would be any systematic differences between the two resulting groups. But researchers would still know each time what the next allocation would be, and could engineer two very different groups of participants. Randomisation avoids this problem.

Randomised controlled trials outside healthcare

Randomised experiments are not unique to medical research. The winners of the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (sometimes referred to, loosely, as the Nobel Prize for Economics) were Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Banerjee, Duflo and Kremer were “randomistas” – development economists who championed the use of randomised controlled trials to make new discoveries for fighting global poverty.

The term “randomista” seems to have been intended, largely, to be derogatory – a bit like calling a painter an “impressionist” – but could equally be worn as a badge of pride. To find out more about why the work of these three mattered so much, read the wonderful profile of Duflo published in the New Yorker in 2010.

Randomised experiments have also transformed the face of digital marketing and online business. Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, Google and many others between them conduct thousands of online controlled experiments annually, involving randomised tweaks to the way different users experience a website or app, and seeking business improvements. These marketing experiments are known as A/B tests.

The ethics of randomised controlled trials

In healthcare research, the randomised controlled trial developed alongside a growing awareness of researchers’ ethical responsibilities. Starting with the publication of the Nuremberg Code after the Second World War, and the subsequent Declaration of Helsinki, there have been attempts to articulate principles for the ethical conduct of clinical trials. These have led to a global framework for legislation on the conduct of drug trials, set out by the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, or ICH for short.

Randomised controlled trials are not without their critics. One of the most vocal opponents of the randomistas was the Princeton economist Angus Deaton, himself a Nobel laureate. Deaton liked to offer the example of parachutes: surely no one would suggest we should conduct a randomised controlled trial to answer the question of whether it was a good idea to have a parachute if you jumped out of a plane? The example seemed damning, but missed the point.

Parachutes

Jumping out of a plane without a parachute has always been considered a bad idea – there was never a particular public health crisis involving people wantonly jumping from planes even after being advised against it. If there had been then it is certainly conceivable that people might investigate education programmes to encourage aviators to take a parachute with them, and perhaps randomised trials would be commissioned to evaluate these programmes.

The ethical point in the parachute example is, incidentally, crystal clear: nobody should involve other people in “research” that involves randomly allocating them to almost certain death. This isn’t a reason to abandon trials – it’s just a reminder to avoid doing unethical research. The ethical scrutiny that follows clinical trials so closely is one of their most admirable features.

A gold standard?

Randomised controlled trials are often described as being a kind of “gold standard” in research, positioned at the pinnacle of some kind of hierarchical arrangement of evidence. This sort of gung-ho smugness has perhaps put a lot of people off. Done well, a randomised trial can provide very persuasive evidence that a new intervention works, but it isn’t always possible to do a trial well (and many are not), or even ethical to do one at all.

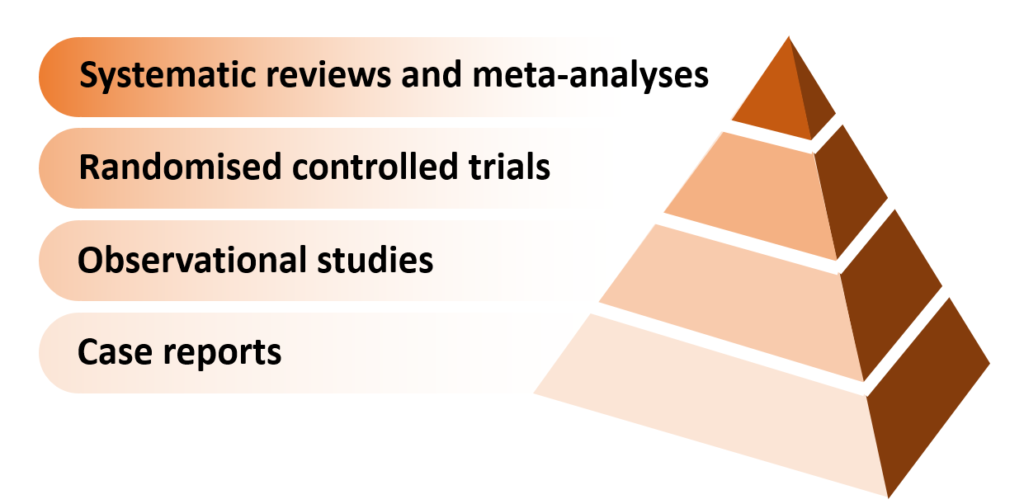

Here is an illustration of the sandstone-carved “pyramid of evidence” which often appears in courses on how to critically appraise published medical research:

And here’s the version created by epidemiologist and statistician, Darren Dahly (the unredacted tweet is here):

Evaluation expert Chris Lysy has floated the idea that the “gold standard” of the randomised controlled trial might simply be a corruption of “Gold’s Standard”, referring to principles championed by Harry Gold, who was a professor of clinical pharmacology at Cornell University from 1947 to 1965 and a pioneer of clinical trials. This is a neat idea, though as yet unproven.

A kind of magic

But love them or loathe them, randomised controlled trials have had a huge impact in helping to shape the delivery of health services over the decades since their introduction, and it seems fitting that randomised trials should have been born in the same year (1948) as the UK’s National Health Service. As a new technology, randomisation was every bit as revolutionary and transformative as the jet engine. Darren Dahly puts it better: randomisation, he says, is “the closest thing we have to magic“.