or The First Stepped Wedge Trial

The first ever stepped wedge trial is also the longest running. The Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study was set up in 1986 to investigate whether vaccination against hepatitis B in infancy could reduce the risk of liver cancer over the next 30 to 40 years of life. The study coined the term “stepped wedge” for a randomised trial with a staggered introduction of the intervention, and still offers a particularly instructive example of this research design.

Background to the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study

In the 1980s there was already evidence suggesting that hepatitis B infection might be linked with hepatocellular (liver) cancer. Vaccinating babies against hepatitis B had the potential to be a highly cost-effective way of cutting cancer deaths. In West Africa at the time, 90% of children were estimated to be infected with hepatitis B by the age of 10, and 20% of these would have been chronic carriers – the main reservoir for infection in the community. But the vaccine was still expensive (more than the cost of all other vaccines currently being given) and the link with liver cancer was unproven.

The Gambia is the smallest country in mainland Africa: its borders follow the Gambia River, and the country is only 30 miles across at its widest. In 1986 it had a population of around 750,000. In 1979 the Gambian government had successfully introduced an immunisation programme (not, at that time, including hepatitis B), which was delivered by 17 regional immunisation teams. This offered an opportunity to conduct a randomised trial of hepatitis B vaccination.

Now, a trial in which individual babies were randomised to hepatitis B vaccine or no hepatitis B vaccine would not have been very practical, given the way that immunisation teams worked on the ground. But randomising each immunisation team either to deliver hepatitis B vaccine or not – in other words conducting a cluster-randomised trial with the teams as “clusters” – was feasible.

The plan of the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study

The plan was this: at the start of the study, one of the 17 immunisation teams was to be chosen at random to deliver hepatitis B vaccinations while the other 16 continued to deliver the original immunisation programme. After 10 to 12 weeks, another, randomly selected immunisation team would start giving hepatitis B vaccinations. Then, after another 10 to 12 weeks, another team, and then another. After 4 years, if everything went to plan, the last of the 17 immunisation teams could start giving hepatitis B vaccinations.

A national cancer registration system was established at around the same time, which (among other things) would allow the researchers to identify all subsequent cases of liver cancer and other chronic liver diseases, and link these with infant vaccination status. The researchers took a number of steps to help them identify their infant participants later in life. This included a unique signature in the form of the scar left by the BCG vaccination, which was given in the left forearm for study infants who also had a hepatitis B vaccination, and in the right forearm for study infants with no hepatitis B vaccination. (After the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study the immunisation teams reverted to giving the BCG in the left upper arm.)

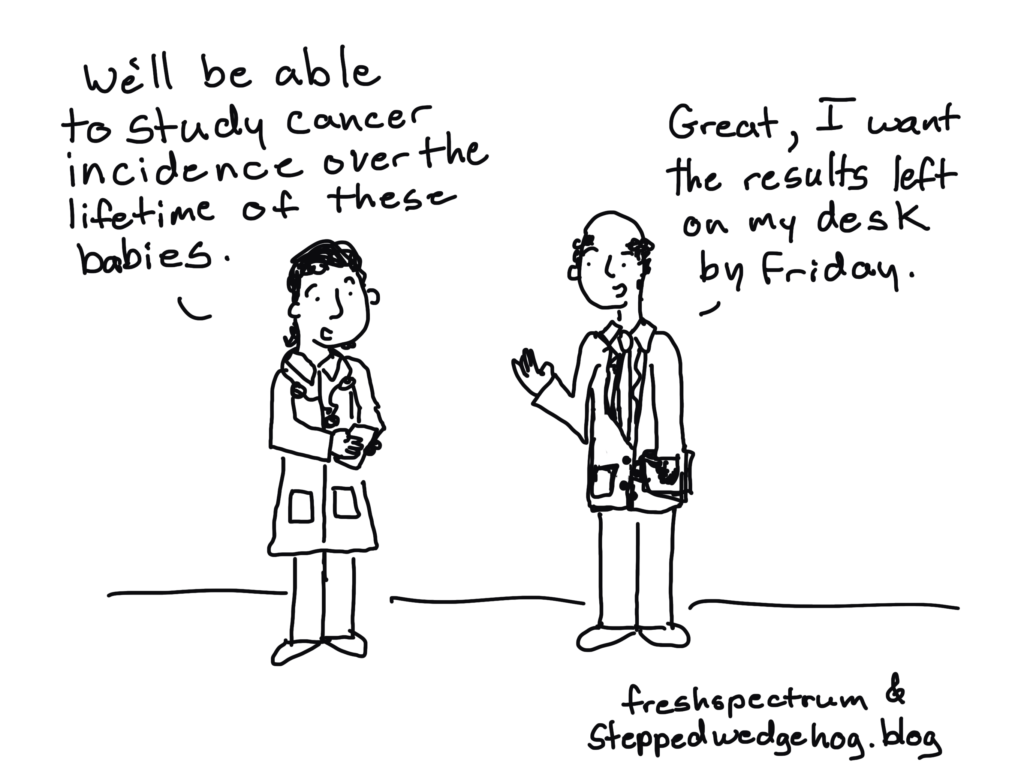

An astonishing vision

To set out to study outcomes some 30 or 40 years after vaccination took a great deal of commitment, forward planning, and determination. The study team’s idea was to weave a randomised controlled trial design into the pattern of the delivery of national immunisation services – to embed, or indelibly imprint an experimental design into the historical public health record – so that they could then return much later, and look at how this had impacted on people’s health in adulthood.

They left some details of the study unspecified, to be worked out later. They trusted that their research question would still be relevant 30 years later. But they were determined to do something, and what mattered to them was to design a study that had randomisation at its heart. It was an astonishing vision.

On some misconceptions about stepped wedges

The study team were not under any illusion, incidentally, that by doing a stepped wedge trial they would be “giving everyone the intervention”. In the description of their research design published in 1987 they explained that during the period over which they would experimentally control the vaccination programme, 60,000 infants would be vaccinated, and 60,000 would not.

That the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study involved implementing first and planning an evaluation later may have given rise to the persistent idea that stepped wedge trials should be used for any evaluation where an intervention was due to be “rolled out anyway”. But the randomised trial design that was embedded into the Gambian vaccination programme did not need to be a stepped wedge trial in particular – it just had to be randomised. The researchers could, in many respects, just as well have randomised half of the immunisation teams to give hepatitis B vaccinations for four years (to 60,000 infants), and half of them not to (another 60,000 infants). So why did they use a stepped wedge?

The real justification for a stepped wedge design

The justification for using a stepped wedge design was not to “give everyone the intervention”. Nor was it because the intervention was being “rolled out anyway”. Instead, by way of justification the researchers cited a World Health Organisation report on preventing liver cancer:

“The best method of ensuring that a protective effect of immunization could be measured would be to use a randomized controlled trial. … Such a randomized trial would present ethical problems if sufficient vaccine were available to treat all newborn children. At present, and probably for the next several years, however, this is not the position as the vaccine is expensive and supplies are limited.”

In other words, a stepped wedge was chosen simply because there were limits on how rapidly the hepatitis B vaccine could be made available to several immunisation teams at the same time (see Reasons for doing a stepped wedge trial).

A non-classic stepped wedge design

In fact, the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study, though it was the first stepped wedge trial, did not follow the “classic” stepped wedge design at all (see What is a stepped wedge trial?). Specifically, it did not start with all of the clusters in the control condition, and finish with all of the clusters in the intervention condition. Instead, the period over which the researchers experimentally controlled the vaccination programme began with one of the clusters already in the intervention condition, and ended with one of the clusters still in the control condition – that is, without access to hepatitis B vaccine.

The diagram below (based on the description published in 1987) helps make this clear.

The legacy of the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study

At the time of writing, in 2020, we are approaching the end of the planned 30-to-40-year follow-up in the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study. A 20th anniversary review of the study, published in 2008, concluded it was on track to deliver the evidence ahead of schedule. For now, we wait. But whether the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study turns out to be the definitive contribution to the study of hepatitis B vaccination as a way of preventing liver cancer, its legacy is in already assured as the template for a research design that seems set on world domination: the stepped wedge.

Sources

The Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study was a joint project by the Gambian Government, the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and the UK Medical Research Council. More detail about the study can be found in academic journal articles such as the following, from which I drew material for this post:

- The Gambia Hepatitis Study Group. The Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study. Cancer Res 1987;47:5782-5787.

- van der Sande MAB, Waight PA, Mendy M, et al. Long-Term Protection against HBV Chronic Carriage of Gambian Adolescents Vaccinated in Infancy and Immune Response in HBV Booster Trial in Adolescence. PLoS One 2007;8:e753.

- Viviani S, Carrieri P, Bah E, et al. 20 Years into the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study: Assessment of Initial Hypotheses and Prospects for Evaluation of Protective Effectiveness Against Liver Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:3216-3223.

- Peto TJ, Mendy ME, Lowe Y, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of infant vaccination against chronic hepatitis B in the Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study (1986–90) and in the nationwide immunisation program. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:7.