If you have an interest in health services research it’s likely that you’ve already come across studies describing themselves as “stepped wedge” trials. This series of posts aims to explain what stepped wedge trials are and why they matter, but also to disentangle some of the myths and confusions that continue to surround them.

The rise of the stepped wedge

Stepped wedge trials have had an extraordinarily rapid rise. The first study to describe itself as a stepped wedge trial began collecting data in 1986 (see The first stepped wedge trial). A review of published trial results and protocols (plans for new trials) from 1986 to 2006 found only 12 stepped wedge trials, including the 1986 trial. Another review just four years later found 13 more. By 2014 the total number had risen to 62. And it continued to grow. At the time of writing, the automated alert that notifies me of academic journal articles with “stepped wedge” in the title sends two or three winging to my inbox every week.

There’s no doubting the impact that this approach is having on research to improve healthcare. But what is a stepped wedge and why are they of such interest?

The short answer

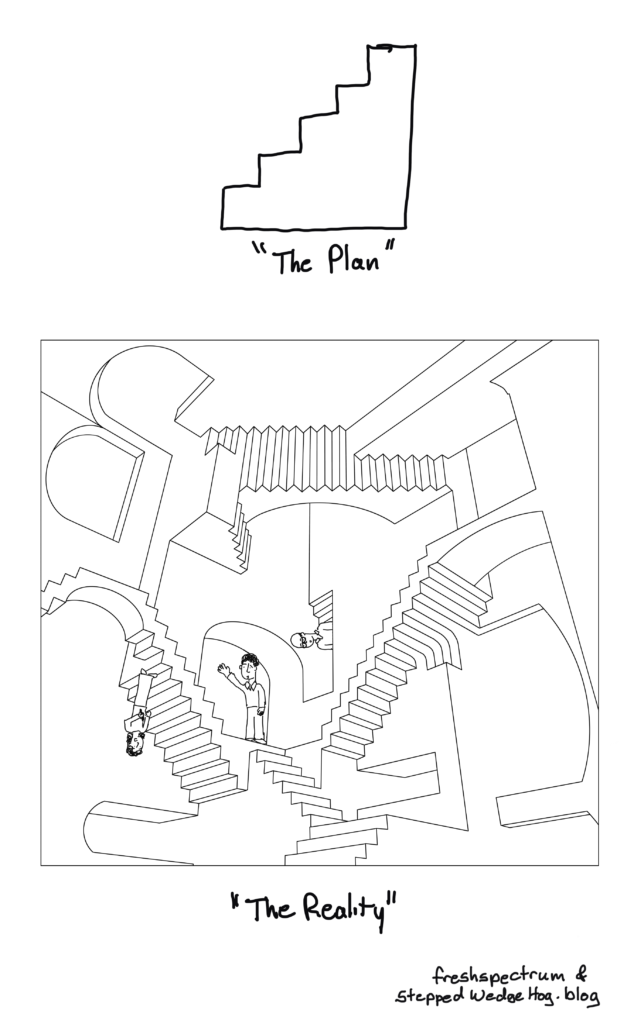

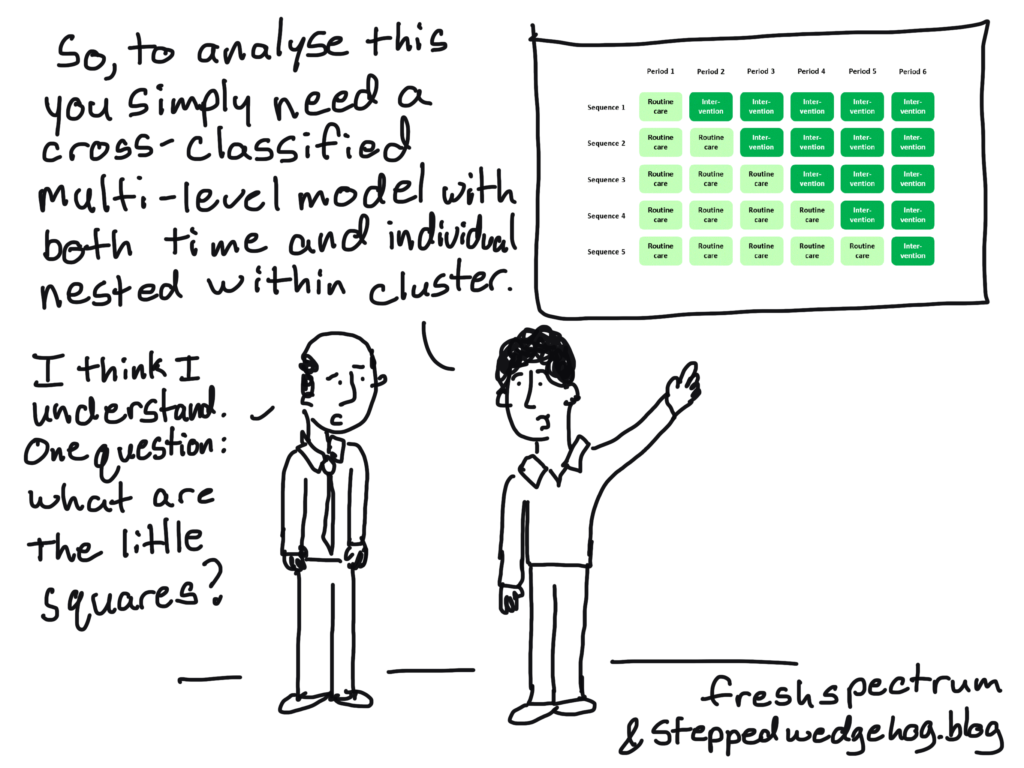

If you’ve stumbled across stepped wedge trials before you may think it’s straightforward and uncontroversial to explain what they are. A stepped wedge trial conducted in a hospital setting, for example, is widely understood to follow a plan that looks something like this:

In this plan, a new, experimental standard of care (or “intervention”) is rolled out to different hospitals according to a staggered timetable, with some hospitals introducing the intervention later than others. The overall time-scale of the trial is divided into a number of “periods”. In each period each hospital is either in “intervention” mode or is still delivering routine care to patients. By the end of the trial, all of the hospitals have moved over to the new intervention.

The unexpected answer

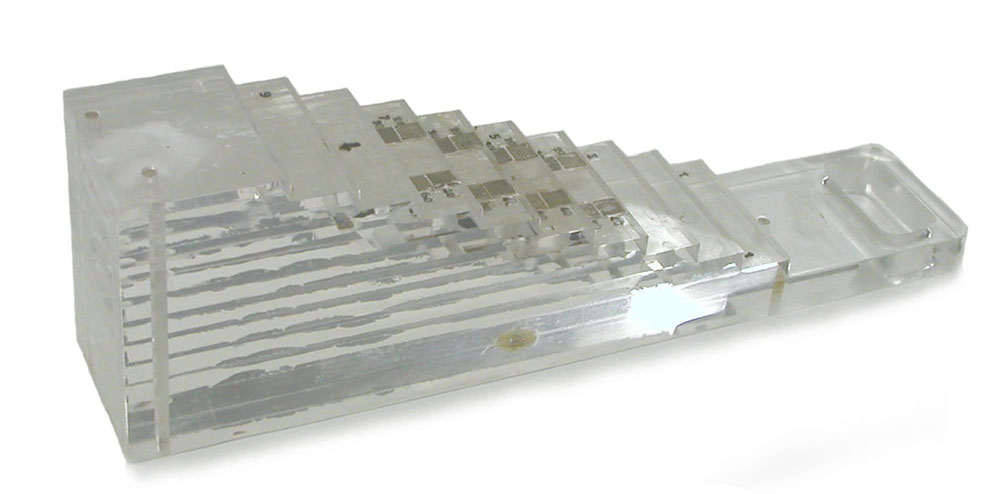

Before the stepped wedge was a type of research design, it had another meaning in the field of medicine. Stepped wedges were (and still are) tools used for calibrating X-ray equipment. Often made from aluminium, they take the form of a wedge-shaped block with steps. As the steps get higher, the total opacity of the block to X-rays increases, and consequently the X-ray image of the block appears as a series of progressively more solid rectangles.

Below is a beautiful image of a perspex stepped wedge, probably home-made in the 1950s or ’60s, from the collection of the Health Physics Historical Instrumentation Museum, in Oak Ridge Tennessee. There are also some lovely photos of stepped wedges in a 1960 article by Seemann and Roth, “New stepped wedges for radiography”.

The long answer

Back to research design: let’s delve deeper into the anatomy of a stepped wedge.

A stepped wedge trial is a type of randomised controlled trial (see What is a randomised controlled trial?). In particular, stepped wedge trials are examples of trials which randomise their participants in “clusters”. The clusters might be geographical regions (see The first stepped wedge trial) or hospitals, for example. In a cluster randomised trial, all the participants from the same cluster are treated in the same way. As long as there are several clusters, some randomised to the new intervention and some to the control, this works very much like any other randomised controlled trial (but do consult an expert if you are planning one).

An example in hospitals

The motivation for randomising in clusters might be that the new intervention is delivered at the cluster level. For example, an evaluation of an intervention in hospitals that involves a training programme for healthcare professionals, with the intention of improving the outcomes of patients attending those hospitals, would most naturally be done by randomising hospitals. Patients who attended intervention hospitals would demonstrate the benefits of the intervention, and patients who attended control hospitals would be the control.

It would be much less practical in this case to randomise individual patients, and to have some health professionals at a hospital who had received the new training and who only treated “intervention” patients, and others who had not had the training who only treated “control” patients. (You might be hard-pressed to prevent these hospital colleagues from sharing notes on their respective approaches.) It would be even more impractical to train every health professional at every hospital, but to ask them to ignore this training whenever they treated “control” patients. Randomising in clusters avoids these difficulties.

A simple plan

Now, suppose you have identified a number of clusters for your trial, and they’re all ready and waiting to be randomised and to start providing you with data. You could randomise half the clusters to the new intervention straight away and half to the control, measure the outcomes of some participants at each cluster in short order, and then finish, congratulating yourself on a job done quickly.

But suppose you’re able to take a little more time. Taking more time over the trial means that you can collect more data – perhaps simply because more people have passed through each cluster by the time the trial has finished, or perhaps because you, the researcher, have the opportunity to go back and revisit each cluster on a number of occasions (see Three kinds of stepped wedge trial).

And taking more time has another advantage: you can experimentally change the conditions at a cluster as time goes by. Suppose the control is the current standard of care delivered to the kind of patient you’re interested in. At the point where your clusters sign up to take part in the trial, they are all (presumably) delivering this current standard of “routine” care. With an extended timetable for your trial you could introduce the new intervention to clusters during the trial, so that even if a cluster begins the trial as a control cluster, it could become an intervention cluster later in the trial. In experimental design this kind of change of conditions during a trial is called “crossing over”.

Having clusters cross over allows you to study the effect of the intervention by studying changes within a cluster, as well as by comparing clusters that are in different conditions at any given moment (see Is a stepped wedge trial really a randomised controlled trial?).

Features of a stepped wedge trial

There are two things that turn the trial described above into a stepped wedge trial. The first is when clusters only cross over in one direction (if at all) – that is, from control to intervention, and never from intervention back to control. Where a trial features this kind of one-way cross-over it is almost always for practical reasons. (Statisticians will tell you that a much better design, on paper at least, is to allow clusters to cross in both directions.)

Stepped wedge trials, with their one-way cross-over, are suited to interventions which might be easy enough to introduce to a cluster, but are much harder (practically or politically) to take away again. These are the interventions that change practice or are difficult to unlearn, or that policy has decreed will eventually be rolled out everywhere.

The second thing that characterises a stepped wedge trial is the number of different schedules or “sequences” to which clusters can be randomised (a “sequence” either specifies that a cluster remains in the control or intervention condition throughout the trial, or that the cluster crosses from control to intervention at a particular moment during the trial). If there are three or more possible sequences then you have a stepped wedge triaI. (If there are only two possible sequences then the design is too simple to need a fancy name.)

Of course, if you have 100 clusters in your trial you could potentially have as many as 100 different sequences, with each cluster randomly allocated to one of these, or you could have a smaller number of sequences with several clusters randomised to each.

The classic diagram

The plan I presented above is cemented in many researchers’ minds as the archetypal scheme for a stepped wedge trial – in fact, it’s where they get their name: the dark or light green blocks in the diagram form a stepped, wedge-shaped pattern.

In this “classic” plan, all the clusters spend some time at the beginning of the trial in the control condition, and all of them cross over to the intervention condition before the trial ends. Successive cross-overs are evenly spaced in time. Each sequence is often assumed to have the same number of clusters allocated to it. But actually there’s no particular reason why any of this has to be the case (see Reasons for doing a stepped wedge trial). The classic plan probably evolved this way just because it looks nice and neat.

In particular, while many people equate stepped wedge trials with the idea of “giving everyone the intervention”, there’s really no reason why a stepped wedge trial has to end with every cluster in the intervention condition, and really no reason why you have to do a stepped wedge trial in order for every cluster to end up in the intervention condition (see You want everyone to have the intervention? You don’t need a stepped wedge trial for that).

Non-randomised studies

Does a stepped wedge trial have to be randomised? That is, do we have to allocate clusters to sequences randomly? Or could we evaluate the effects of the intervention by observing outcomes of patients during the natural course of a real-world rollout of the intervention, with hospitals or other decision-makers choosing their own schedules?

Certainly this kind of study is possible, and certainly we could learn something from it, although randomisation (when it is possible to do) will still have benefits (see What is a randomised controlled trial? and Is a stepped wedge trial really a randomised controlled trial?). I think it would be over-complicating things to give a non-randomised study like this a complicated-sounding name. It’s simply an observational study – a study of what actually happens – and that’s all the description it needs. For me, “stepped wedge” should imply randomisation.

So, should I do a stepped wedge trial?

The design of any research study should be led by the problem and by practical constraints. If you’re drawn to a stepped wedge design because they’re fashionable, or because people who don’t know the context for your research tell you that’s what you need, you may be putting the cart before the horse.

There are good reasons for using a stepped wedge design (see Reasons for doing a stepped wedge trial) but there are also bad ones. In particular, a stepped wedge trial is not the only way to ensure that everyone gets an intervention within a certain time-frame. You should only add complexity to your research design because you have to, bearing in mind there are also virtues in getting answers quickly and keeping things simple.